Why Build This Chess Engine?

I’ve been fascinated by chess since I started playing around seven years ago. This is actually my third try at building a chess engine. The first two fizzled out, but this time, I committed more seriously and finally saw meaningful progress. The name of this engine is Foresight and this is the first part in a series of articles articulating my journey.

The best way to learn is by doing. You think you understand something as simple as how to sort a list of numbers until you actually implement a high-performance sorting algorithm and compare it to state-of-the-art solutions. You then realize there are CPU-level optimizations, cache-aware designs, and memory access patterns that you wouldn’t discover without hands-on exploration.

Similarly, I had recently read an excellent book on Java concurrency, and I wanted to apply that knowledge in a domain I had decent familiarity with: chess engines.

Initially, I thought it would be cool to parallelize the alpha-beta minimax algorithm and enjoy performance gains. It turns out, though, that alpha-beta pruning is a peculiar algorithm. Beyond a point, parallelism yields diminishing returns and, paradoxically, can slow down the engine, depending on the number of cores and the specific parallel strategy employed.

How Does a Chess Engine Work?

At its core, a chess engine evaluates a board and decides the best move. Chess has a 8×8 grid board with a fixed starting position. Each player has the same number of pawns ♙, rooks ♖, bishops ♗, knights ♘, queen ♕ when the game starts. Each of these piece move uniquely and the goal of the game is to checkmate the enemy King. Alternately the game can end in a draw due to insufficient material or Fifty-move_rule.

Unlike games like Poker that involve hidden information, chess is a game of complete information. Both players see the entire board.

The primary goal in chess is simple: checkmate the opponent’s king. While checkmates can sometimes be forced with a known sequence of moves, most positions in real games are too complex for such deterministic conclusions.

Is Chess already solved?

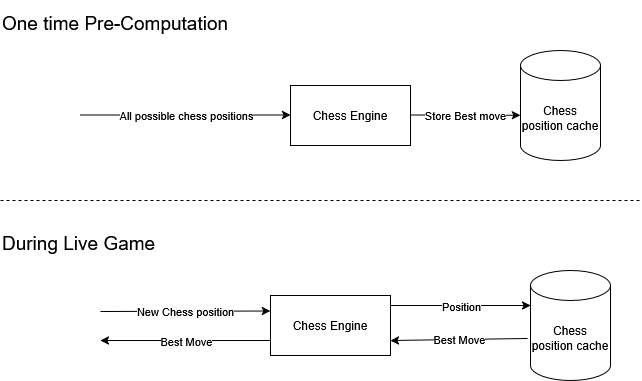

On the surface Chess is like Tic-Tac-Toe : both are a 2D complete information, turn based, zero-sum games. Even a human can become perfect in Tic-Tac-Toe in less than a day i.e always playing the best move in given position. We all know Chess Engine computers are extremely strong now. So, do we already have a database where we have stored the best moves for all possible positions. Above statement has been visualized as follows:

Tic-Tac-Toe has only 765 unique positions, so it’s feasible to store the best move for every scenario. In contrast, chess explodes in complexity.

After just six moves from the opening position, there are over 10^7 unique positions. Storing them all would need at least 1.4 GB memory (assuming 140 bytes per board state), and that’s just scratching the surface.

The total number of distinct chess positions is estimated to be over 10^45.

Chess is not a solved game like Tic-Tac-Toe. Solved as in we have not pre-computed all possible positions. We will also learn that it’s practically impossible to find the best move for most chess positions and have to always settle for an approximation.

So brute-force pre-computation is off the table. Instead, engines dynamically evaluate each board state and the above architecture is not possible in practice.

Chess Algorithm

If Chess is a computable problem, then we should be capable of writing an algorithm to find the best move, given a chess position, we will make all possible moves and will find the move where we get the best score, here is the algorithm:

function FIND-BEST-MOVE(board, isWhite):

bestMove ← null

if isWhite then:

bestScore ← −∞

else:

bestScore ← ∞

for each move ∈ ALL-LEGAL-MOVES(board) do:

MAKE-MOVE(board, move)

score ← FIND-SCORE(board, ¬isWhite)

UNDO-MOVE(board, move)

if score > bestScore and isWhite then:

bestScore ← score

bestMove ← move

if score < bestScore and not isWhite then:

bestScore <- score

bestMove <- move

return bestMove

White will try to find a position with the maximum score leading to the checkmate of the black king and therefore avoid the move leading to the checkmate of the white king and vice-versa.

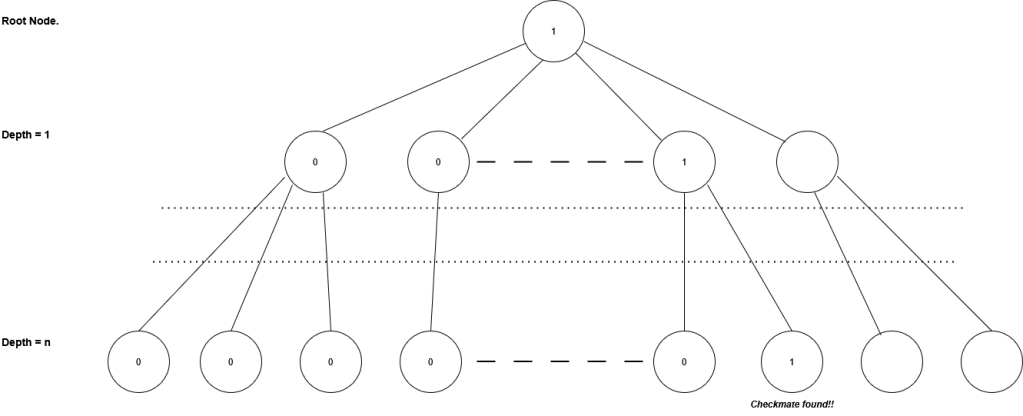

Now, all we need to do is to define the FIND-SCORE function, since we know that there is only one objective in chess – to checkmate the opponent’s king. Score is 1 when white king is checkmated, -1 when black king is checkmated and 0 in case of a draw position. Possible states of a board: {0, 1, -1}.

function FIND-SCORE(board, isWhite):

if WHITE-CHECKMATED(board): return −1

if BLACK-CHECKMATED(board): return 1

if DRAW(board): return 0

if isWhite then:

bestScore ← −∞

else:

bestScore ← ∞

for each move ∈ ALL-LEGAL-MOVES(board) do:

MAKE-MOVE(board, move)

score ← FIND-SCORE(board, ¬isWhite)

UNDO-MOVE(board, move)

if isWhite then:

bestScore ← max(bestScore, score)

else:

bestScore ← min(bestScore, score)

return bestScore

There is nothing wrong with this algorithm, except that when you run this algorithm: you are basically trying to find the move which leads to checkmate and this recursive algorithm in practice will take an impractical time to execute since chess positions are rarely instantly leading to checkmate in X moves. Also lets assume that the checkmate takes 40 moves to reach, this algorithm will need to evaluate an ungodly number of positions (3540 positions considering an average branching factor of 35) and will take years in practice to evaluate that checkmate.

Assume F(board, side) is a computable algorithm for a chess engine, here’s what we can do to improve the above algorithm is make few assumptions based on practical chess play:

- The FIND-SCORE() algorithm practically can’t be infinitely recursive, we would like cutoff this evaluation this evaluation at a certain depth and it is a reasonable assumption that looking at X moves ahead will lead to better evaluation than looking at Y moves ahead if X>Y.

FIND-SCORE(depth = 10) >> FIND-SCORE(depth=5) - Any chess player knows that much before checkmates come to picture, a player will try to capture as many pieces of the opponent as possible while losing as little of your own pieces. Also practical chess playing shows that certain pieces are more valuable than others like queen is more valuable than a rook and a bishop is more valuable than a pawn.

We will create another function FIND-SCORE-STATIC-EVALUATION(), which also considers the individual pieces on the board, and other custom features like mobility of pieces which humans have observed

So, if the position is not a checkmate, we want to use all the pieces on the board to find a net score with the assumption that having more pieces on the board will eventually lead to checkmating the enemy king. tldr: having more pieces on the board compared to the opponent has a high correlation to checkmating the enemy king.

FIND-SCORE() ≈ FIND-SCORE-STATIC-EVALUATION()

In the upcoming articles we will delve into how to design the FIND-SCORE-STATIC-EVALUATION() using techniques like bitboard representation, bitwise operations and using alpha-beta pruning among other techniques to efficiently prune the move tree.